A new scepticism and a look at my probable teeth

A friend told me the other day that he was feeling a bit of "AI fatigue" after the last few weeks, which I can well understand. It has all been a bit much. From the Sony World Photography Award to the Amnesty Norway fake photo campaign to the Pentagon explosion deepfake in barely two months. For photography, it feels like the whole industry has woken up to the possibilities and threats of AI, and it all seemed to run under the headline:

AI-generated images are so good, even AI has trouble spotting some.

At least that's how The Wall Street Journal put it in an article about AI tools designed to help us distinguish generated photos from real ones. Tools such as AIorNot.com or Hivemoderation's AI content detector, and the difficulties these programs have in keeping up with the rapid improvement of the image generators themselves. Let's face it, we need these programs to work, because looking for squishy text and too many fingers won't keep us safe for long: at this pace, it will be gone tomorrow. Oh wait, it's already gone.

This Monday I went to a talk by the German photographers' association FREELENS about AI in an editorial context, and what became clear is that we don't have a frame of reference for this development. We don't have workflows or guidelines on how to deal with the suspicion of ubiquitous fake content in our day-to-day work. Who will be responsible for identifying and sorting out deepfakes in photography? Is it the photo editor who decides what gets published, the photo agency that selects which images are distributed to the market, or do we feel we can rely on photojournalistic ethics in a system of trust?

I have noticed a fundamental change in the way I look at photography. I often find myself looking at images, especially the striking and improbable, with a new and palpable distrust. I think I am not alone in this - I see comments declaring images fake all over social media. A newspaper photo editor I know told me the other day that she found herself suspiciously checking every single shot in a submitted story for discrepancies. And this isn't paranoia: in an article on Vox.com, Shirin Ghaffary quotes Europol predicting that up to 90 percent of content on the internet could be created or edited by AI by 2026. That's in three years. No amount of fact-checkers will be able to sort through this mess.

However, Malin Schulz, art director and member of the editorial board of DIE ZEIT, pointed out out in Monday's talk how important trust in sources is for journalistic reporting, and how newspapers whose visuals are based on their own photo productions and commissioning of photographers (as opposed to newspapers that primarily license existing material) could benefit from this investment in the future. After all, if the editorial team and picture editors are in direct contact with the photographer, the writer, and the protagonists, and if they know the story, the locations and the context, the results are almost guaranteed to be reliable. Fact-checking suspect agency images, on the other hand, requires a whole new infrastructure in both newsrooms and photo agencies, and the question is how this can this be done with the limited resources that most newspapers struggle with today?

On that note, please read Shirin Ghaffary's article, which gives a very insightful overview of current approaches to labelling AI content.

If you were hoping that in the future we would only have to distinguish between "real" photos and generated ones, rest assured that it will be trickier than that. The internet has had a lot of fun with Adobe Generative Fill. Particularly interesting are the results you get when you give the program very little information - for example, very close crops . I tried it too, you can check out my probable AI teeth in the first photo of this post - they look pretty friendly, I think.

An interesting practical application of Gen AI comes from Polish street photographer Hubert Napierala. Personal rights are a big issue in street photography, especially in Europe with the GDPR data protection law. Getting permission is difficult to impossible, especially in crowds. So Napierala came up with the idea of using AI face-swap via Dall-E in his images. That way, no one looked like themselves and he felt that the new faces didn't compromise the shots. His street photography group on Facebook didn't think it was funny and kicked him out. Although I am not convinced that the images are necessarily better after the swap, I am tempted by the idea of rendering people anonymous in this way if there is a need. The Amnesty case was also interesting in this regard when they cited witness and victim protection considerations in their rationale for using AI images in their social media campaign (they mentioned that showing real protesters would put them at risk of possible state retribution).

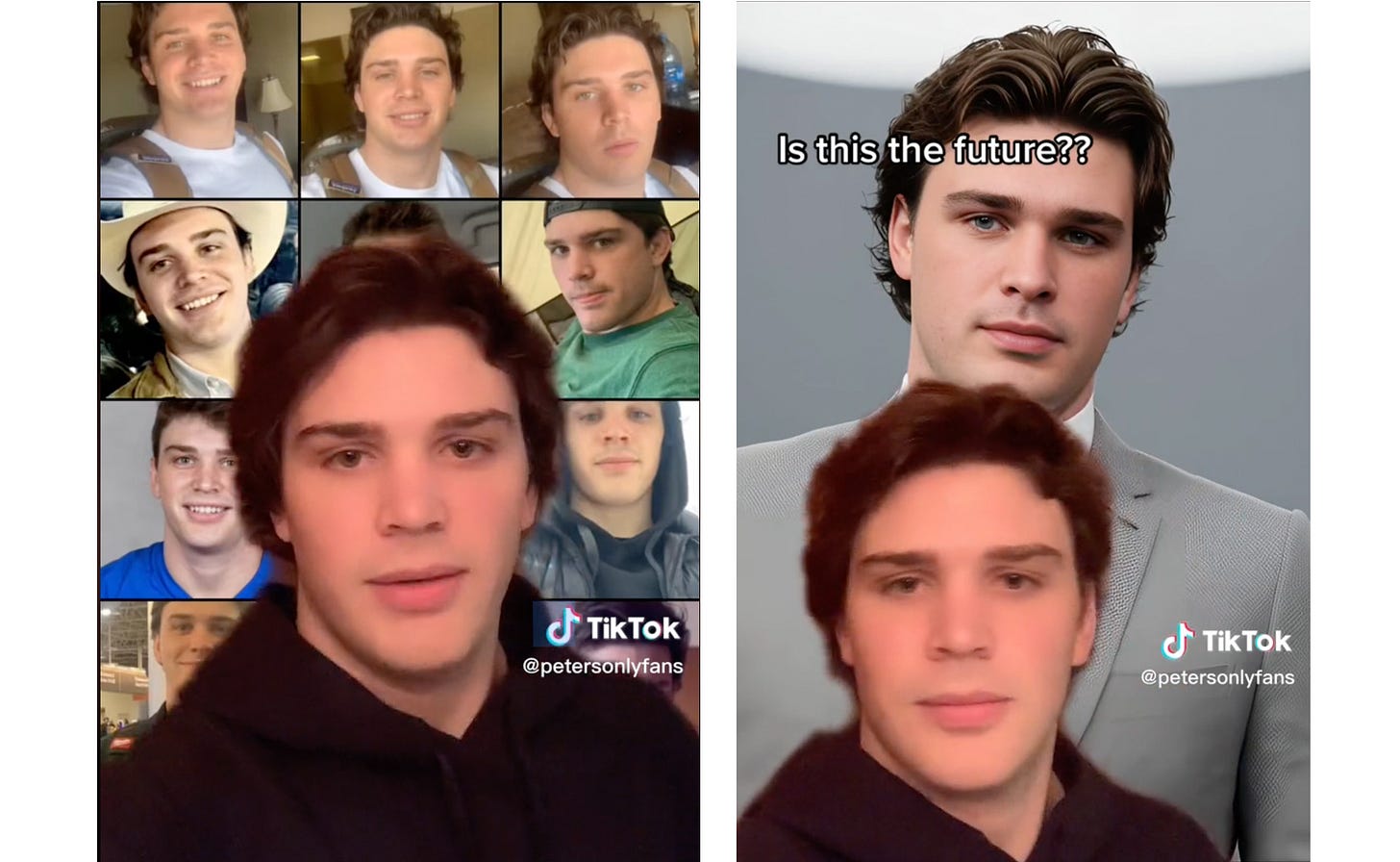

Another example of how hybrid photography could be in the future is a program called Headshot-Pro, which aims to save companies and individuals the trouble of hiring a portrait photographer. You can upload a series of selfies and snapshots, and the output is a “professional corporate headshot”.

It's not very natural yet - but it's not bad, is it? I'm just not sure what it is. A portrait? A posing avatar?

In the 1990s TV show The X-Files, and I remember there was a tool that allowed agents Mulder and Scully to zoom in on surveillance footage: they'd select a section of a heavily pixelated source image and zoom in until the suspect's and/or alien's face was clearly visible. It used to make me laugh, because any image professional knows that all you're going to see are bigger pixels. At least that's the way it used to be.

I recently tried an AI upscaling tool. I used it to upscale an 800KB image to A1. No kidding. The faces ended up looking a bit crazy, in fact the whole image looked like a heavily sharpened and post-produced beer ad, with invented details that were convincing: the people still looked similar, their teeth went from grey mush to defined teeth, green dots to defined leaves. In seeing these results, I suddenly understood something very obvious. Generative AI throws overboard a central tenet of my belief system, the belief that you can't retrieve information that isn't there. Well, now you can.